In war, a “casualty” is a soldier who suffers any condition that puts him or her out of action, which includes being killed as well as wounded, whether in battle or by accident. During the four days in which the 35th Division advanced the line, it suffered 8,023 casualties. September 29, 1918, the fourth day of fighting, would be the 35th’s bloodiest day.

So many casualties would reduce a full-strength division by one quarter. However, according to Kenamore, most of the 35th’s casualties came from front-line troops. Since the division began the battle undermanned, its four infantry regiments were reduced to half strength. (241)

The division also went into the battle with half the quota of officers for the troop count. So, the high casualty rate put a particular strain on the leadership. Even with staff officers, rounded up and sent forward, by the previous day some battalions were commanded by lieutenants.

A thinning olive drab line held back the enemy the morning of the 29th. A heavy rain fell on Montrebeau Wood. Beneath the dense canopy, darkness pervaded, lit up by occasional enemy artillery fire. The day’s orders were to attack at 5:30 a.m. The objective: Exermont.

The village of Exermont lay in a ravine running east-west across the division sector. Of the town, Kenamore writes, “Tolerably well placed for defense…, it was ringed three-quarters of the way round with cannon and machine guns.” (205)

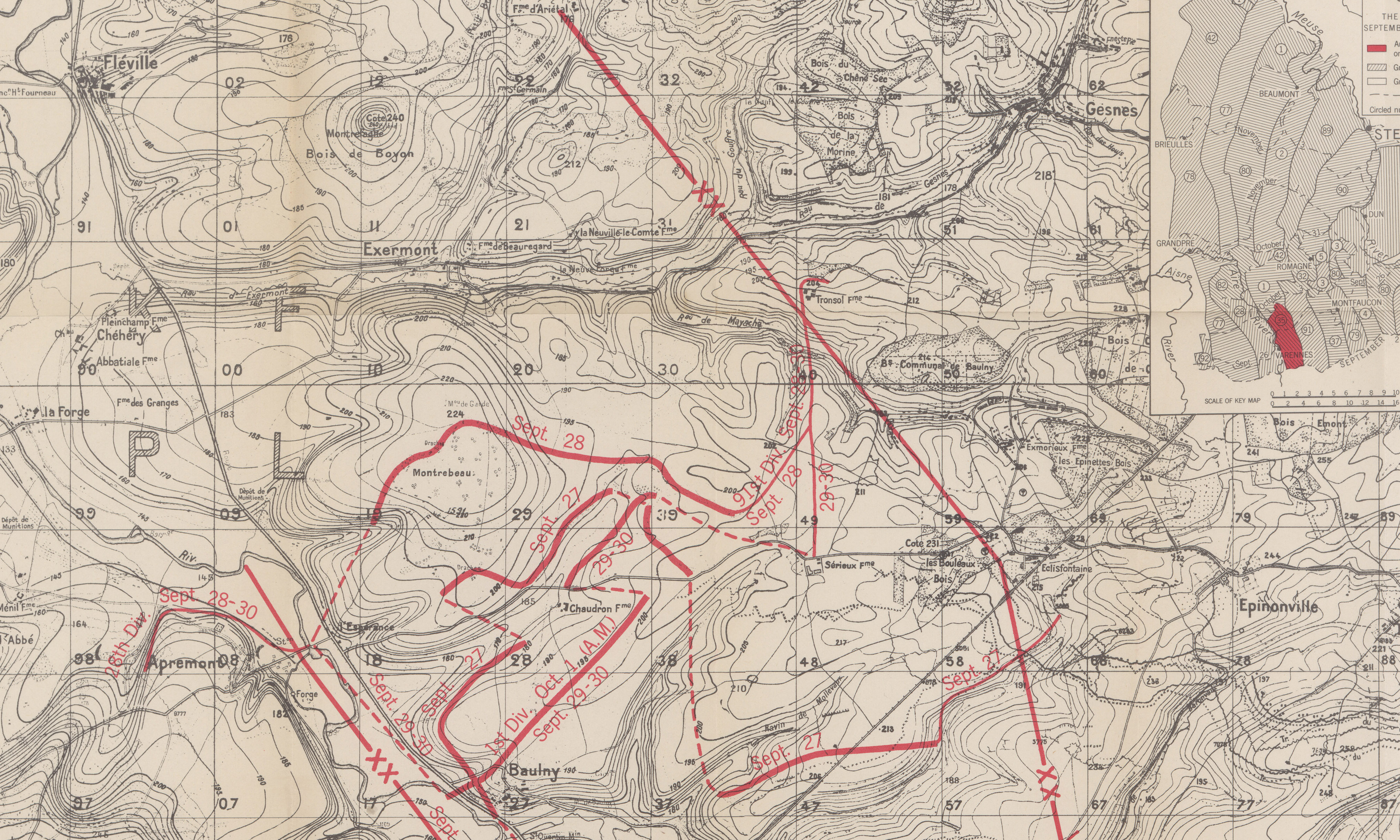

What’s more, from Hill 240 behind the town (“Côte 240” on the map) came much of the artillery fire that had so devastated the ranks in previous days. Today, the troops would be in range of machine-gun fire from those heights as well.

Map section, September 29, 35th Division, Grange le Comte Sector, Meuse-Argonne, American Battle Monuments Commision 1937

Map section, September 29, 35th Division, Grange le Comte Sector, Meuse-Argonne, American Battle Monuments Commision 1937

The plan for the 137th was to attack in two waves. Major Kalloch, who had been the division intelligence officer the evening before, would lead the first wave. The units were so mixed on the division sector’s left half we can no longer speak of battalions. The officers just rounded up what men they could find to carry out the mission.

Major Kalloch put 125 men “mostly of the 137th regiment” (Kenamore 205) into an attack formation. At 5:30 a.m., he waited for the artillery barrage promised by the division orders. Four minutes later, the major led the men from the concealment of Montrebeau Wood without the friendly artillery barrage.

Kalloch advanced through heavy artillery and machine-gun fire. As the men would destroy one machine-gun nest, other enemy gun crews were setting up on both sides of their skirmish line. Taking out these nests one after another, Kalloch and his men reached the ravine west of Exermont, loses mounting. The major ordered the men to dig in.

“There was no sign anywhere of the supporting wave Col. Hamilton [commander 137th Regiment] was to bring out, so Kalloch sent two runners, one a few minutes behind the other, to say that he could go no farther without support.” (Kenamore 206)

When the second wave, led by Major O’Connor under Colonel Hamilton’s orders, emerged from Montrebeau Wood, it was full daylight. O’Connor’s troops took artillery and machine-gun fire from three sides. “The men were willing and brave, but much disorganized, largely, I suspect, through their great physical weariness. The officers were unable to maneuver them. When they reached the top of the rise and got the full force of the fire, they seemed just to fade back into the woods.” (Kenamore 207)

At 8 o’clock, with more enemy machine guns filtering down the slope before his line and without reinforcements of his own, Major Kalloch was forced to retire with his troops from Exermont.

Later in the morning, larger elements of the 139th, on the division left, and the 140th, on the right, were successful in an assault on Exermont. Kenamore describes the charge in the face of enemy fire:

“In the stunning, dumbing gust of war the men sensed with their bodies rather than their minds, that death was pouring past them in a flood. As if they were walking forward through a driving hailstorm they turned their faces to leeward and, leaning forward against the blast, pushed ahead with the point of shoulder offered to the gale.” (209)

They took the village and held a line on the southern slope of Hill 240. However, reinforcements were not forthcoming, and communication was difficult with commanders to the rear. The 140th regimental commander wasn’t even aware that part of his regiment had made it so far forward.

When General Traub, division commander, came up around 11 o’clock to assess the situation, he found the division strength much depleted, its units disorganized. In a message to Corps Headquarters, the general wrote: “Regret to report that this Division cannot advance beyond crest south of Exermont. It is thoroughly disorganized through loss of officers and many casualties, for which cannot give estimate, owing to intermingling of units. Recommend that it be withdrawn for reorganization and be replaced promptly by other troops in order that the advance may be continued.” (Quoted in Kenamore 217)

Soon after, the division’s 110th Engineer Regiment received orders to construct a defensive line below the ridge running northeast from Baulny. Forward units were then ordered to withdraw to that line. The order to withdraw was delivered by runner.

“Where’s Private Potts?”

“Here, sir!”

“This message is for Colonel Hamilton, 137th, in Montrebeau Wood. We’re pulling all forward units back to the Engineers’ line. The 137th is to cover the withdraw of troops from Exermont before pulling back. If the colonel doesn’t get the word A.S.A.P., the troops from Exermont will be sitting ducks. Do you understand?”

Potts, who leapt from the shell hole at “A.S.A.P,” shouts, “Understood, sir!” over a shoulder.

Where any-sized formation of men must spread itself out to advance through enemy fire, as well as arrive in force at the attack point, a lone man may choose a narrow path and not necessarily the most direct route to the destination. He negotiates the terrain, dodging enemy fire, exposing himself as little as possible, and taking advantage of battlefield distractions.

Message delivered, the messenger may have withdrawn with the troops. A “withdraw” is a tactical movement where one-half a unit—say, a six-man squad—fires toward the enemy’s position to keep their heads down (this is called “suppressive fire”), while another squad moves back a few meters. Then, this second squad lays down suppressive fire, while the first squad moves back. By this leap-frog action, the unit may cede ground without over-exposing itself to enemy fire.

Far enough removed from the German line, Private Potts and the rag-tag platoon he accompanies hasten south. A hill rises to one side. Below its crest, a man crouches at the edge of a shell hole, looking through field glasses to the north, steel helmet cocked back. Another soldier adjusts dials on a field telephone, while a third approaches from the south and hops into the hole with a spool, wire trailing behind.

Potts calls out, “Hey, fellows!”

The crouching man lowers the field glasses, revealing a triangle nose and round-rim spectacles.

“We’re falling back to Chaudron Farm. The Germans’ll be here any minute.”

The hole’s occupants jump into activity, gathering equipment. The man snaps orders while stowing the field glasses in a pack. Potts hurries on.

That night, the remains of four infantry regiments and one engineer regiment defended the prepared line against counterattack. The officers and men didn’t know it yet, but the 35th Infantry Division had made its last advance of the Great War.

My great grandfather, like many veterans, didn’t talk much about his wartime experience. His family has only his discharge paper and a few anecdotes.

One hundred years later, I’ve discovered a few documents that bear his name. From draft registration to discharge, I’m following the paper trail of B. F. Potts’s journey to the battlefields of the Great War in France and back home again.

Previous articles:

“Well, Daddy, what did you think about France?”

“It's a very muddy place.”

Benjamin Franklin Potts Registers for the Draft

As the Great War thundered across the fields of northern France, ten million American men, ages 21 to 30, signed their names to register to be drafted into military service.

Military Induction and Entrainment

“I, Benjamin Franklin Potts, do solemnly swear to bear true allegiance to the United States of America, and to serve them honestly and faithfully, against all their enemies or opposers whatsoever…”

“If it moves, salute it. If it doesn’t move, paint it!”

Embarkation, the Tunisian, and the Bridge of Ships

In his first ocean voyage, B. F. Potts crossed the submarine invested waters of the North Atlantic in a convoy of steamers escorted by a warship.

Enterprise, Tennessee: The Town That Died

Grandpa owned matched pairs of horses. Him and the boys [Ben and his brothers] cut and snaked logs out of the wood to the roads. He got a dollar a day plus fifty cents for the horses.

Rendezvous with the 35th Infantry Division

“Some of the guys disobeyed orders, went into the town, broke into a bakery, and stole all the bread and baked goods…”

The battle of Saint-Mihiel (September 12-15) would be Pershing’s first operation as army commander. He assigned the 35th to the strategic reserve, whose purpose is to replace a weakened unit or to fill any gap in the line created by the enemy.

“Private Potts, how tall are you?”

The soldier, looking into a button of the captain’s coat, says, “Five foot three, sir.” The wide brim raises.

On the front now, the 35th was in range of artillery fire, and enemy planes made nighttime bombing raids over the countryside.

Planning the Meuse-Argonne Offensive

On the left, the 137th would take the “V of Vauquois,” a formidable network of trenches, zig-zagging from the hill’s west flank to the village of Boureuilles, a mile away.

The gun jumps, the earth shudders, a shock wave shatters the air and accompanies a roar that bursts between the ears. Powder fumes permeate the air. Explosions count seconds across unending darkness.

…up until 7:40 a.m. when the rolling barrage ceased, we can follow Private Potts’s movement across the battlefield.

Scrawling in a notepad, the commander tears the sheet, folds it, and thrusts it into the runner’s hands.

“Potts, take this message to brigade. Tell them we need artillery now. Go!”

“Let him lie in an artillery shower all night, if you must. But do not disturb a soldier’s sleep, sir, with your orders that change from one minute to the next!”

By morning’s end, the intermingled 137th and 139th regiments gained 500 meters and dug in before Montrebeau Wood. Through the woods and German machine-gun nests and sniper fire, the men fought in the afternoon.

“When I asked him [Grandpa Ben] if he killed anyone, this is what he told me…”

Next date:

September 29—Clive Brake Boards the Leviathan

September 30—The Engineers’ Line