September 5, 1918, Clyde Brake Potts followed his two older brothers’ steps to the Houston County Courthouse, where he took the oaths of an enlisted man in the United States Army. Unlike his brothers, who received military training at Camp Gordon before going overseas to combat the enemy, Clyde Brake neither went to Camp Gordon nor received military training. Fortunately, he didn’t see combat, either. His voyage to France, however, was a nightmare.

The 57th Pioneer Infantry Regiment was organized in February 1918 at Camp Wadsworth, South Carolina, made up of 500 officers and men from the 1st Infantry Vermont National Guard. After six months of training, they were due to ship out in September.

To bring the unit up to strength, twenty-five hundred Tennessee draftees were assigned to the 57th on September 12. Private Clyde Brake Potts became a member of Company G, which was part of Second Battalion. Eleven days later, the regiment entrained to Camp Merritt outside of Hoboken to prepare for boarding on the 29th.

In a Vermont newspaper article, published in 1920, the regiment’s personnel adjutant at the time, Captain E. W. Gibson, recounts the trans-Atlantic voyage. Describing the march from Camp Merritt down to the docks, where ferries would take them to the Leviathan, Gibson writes:

“The second and third battalions marched out from their barracks about 1 a.m. on the morning of the 29th of September. We had proceeded but a short distance when it was discovered that men were falling out of ranks, unable to keep up… The column was halted, the camp surgeon was summoned…”

The diagnosis: Spanish flu.

The 1918 Spanish influenza pandemic became the most deadly ever recorded. Caused by the H1N1 influenza virus, it was named after the country that seemed to have been hardest hit. However, this is an effect of censorship. Warring nations suppressed news reports about the virus’s impact at home. Neutral Spain did not.

In fact, Spanish flu was indifferent to national borders. From 1918 through 1920, it circled the globe in waves, infecting a third of the world’s population. With a mortality rate of at least ten percent, it killed up to one hundred million—five percent of humans on the planet at the time.

Its symptoms were like any flu: fever, aching joints, nausea, and diarrhea. Unlike most flu viruses, which kill more infants and elderly, Spanish flu killed more otherwise healthy adults. Many victims developed pneumonia. Often, prior to death, a victim turned blue, suffocating as the lungs filled with blood.

Despite a military organization’s dependence on strict adherence to orders, leaders are encouraged to analyze a developing situation, and if necessary, disobey an order. In that case, the leader takes the responsibility of subsequent outcomes, whether good or bad—the results of his or her “command decision.”

In the 57th’s case, while common sense might have dictated immediate quarantine, no operating order countermanded the regiment’s orders to embark. Some would argue the commander failed to make a command decision. Be that as it may, the sick were carried back to the camp hospital, and the 57th Pioneer Infantry Regiment boarded the Leviathan as ordered.

The Leviathan was not only the largest ship on the seas, she was also the fastest. At twenty-two knots, she would cross the Atlantic in eight days. German U-boats, much slower, would have to be in her path to fire upon her. No need for a warship escort, the Leviathan steamed out of New York’s Lower Bay and set out across the Atlantic Ocean alone.

Although a similar flu outbreak aboard the President Grant claimed more lives, Alfred W. Crosby uses the Leviathan’s September 29 voyage in America’s Forgotten Pandemic: The Influenza of 1918 (2003), because “the Leviathan’s records are more complete, and her story is gruesome enough to illustrate what the very worst was like.” (126)

The quarters were cramped. The vessel carried 6,800 passengers as a peacetime cruise liner. As a troop transport, bunks were stacked four high. With the 57th’s 3,400 men, an additional 6,000 troops—mostly draftees, 2,000 crew, and 200 Army nurses, the total passengers aboard the Leviathan approached 12,000.

By the time the men found their bunks, more of them were falling ill. The nurses, on their way to Army hospitals in France, went to work, assisting the ship’s overwhelmed hospital staff. By the evening of the 30th, seven hundred flu cases spilled out of sick bay. One man was already dead.

Crosby cites an official report, which describes the scene on the night of September 30:

“Pools of blood from severe nasal hemorrhages of many patients were scattered throughout the compartments, and the attendants were powerless to escape tracking through the mess, because of the narrow passages between the bunks. The decks became wet and slippery, groans and cries of the terrified added to the confusion of the applicants clamoring for treatment…” (Quoted in Crosby 132)

Captain Gibson uses the same words in his 1920 news article, adding:

“Everyone called for water and lemons and oranges… but within a few minutes of the first distribution of the fruit, the skins and pulp were added to the blood and vomitus upon the deck.”

Crosby continues:

“The troop compartments of the Leviathan were so crowded that the slightest inattention to daily cleaning would quickly turn them into impassable sties especially with flu causing nosebleeds among 20 percent of the sick and seasickness causing vomiting among the sick and healthy.” (132)

On the third morning at sea, when their officers ordered the men to clean the troop compartments below decks and carry out the sick and the dead, they refused. When a soldier disobeys a lawful order, it’s called insubordination. Punishment can be as severe as time in jail with hard labor. When more than one soldier disobeys a lawful order, it’s called mutiny and is punishable by death.

By that evening, October 2, a second victim succumbed to the flu. The next day, three more. Seven more the day after.

Then, from the ship’s War Diary, October 5:

“Total deaths to date, 21. Small force of embalmers impossible to keep up with rate of dying.”

October 6:

“Total dead to date, 45. Impossible to embalm bodies fast enough. Signs of decomposing starting in some of them.” (Quoted in Crosby 133)

Estimates put the total flu cases during the voyage at 2,000 out of 12,000 aboard. Ninety of those died.

October 7, the ship arrived at Brest. After disembarking, Private Clyde Potts marched, with those of the 57th who were able, through pouring rain to a muddy camp five miles away. On the march and at the camp, more men fell. Crosby counts upwards of 170 flu deaths from the division after the landing (134-135).

Clyde Brake escaped the Spanish flu. By the end of October, he was far from the front, near Le Mans. There, we lose his trail until September the next year.

According to The US Army in WWI: Orders of Battle (Rinaldi 2005), the 57th Pioneer was due to be converted to the 398th Infantry when the Armistice was signed. A fellow September 5 draftee, Henry F. Forte, wrote in a 1975 letter that he was transferred to the 329th Regiment, 83rd Infantry Division, in the days prior to November 11. The 83rd Division, in the Le Mans area at the time, was a “depot division,” from which troops were rationed out to other units as replacements.

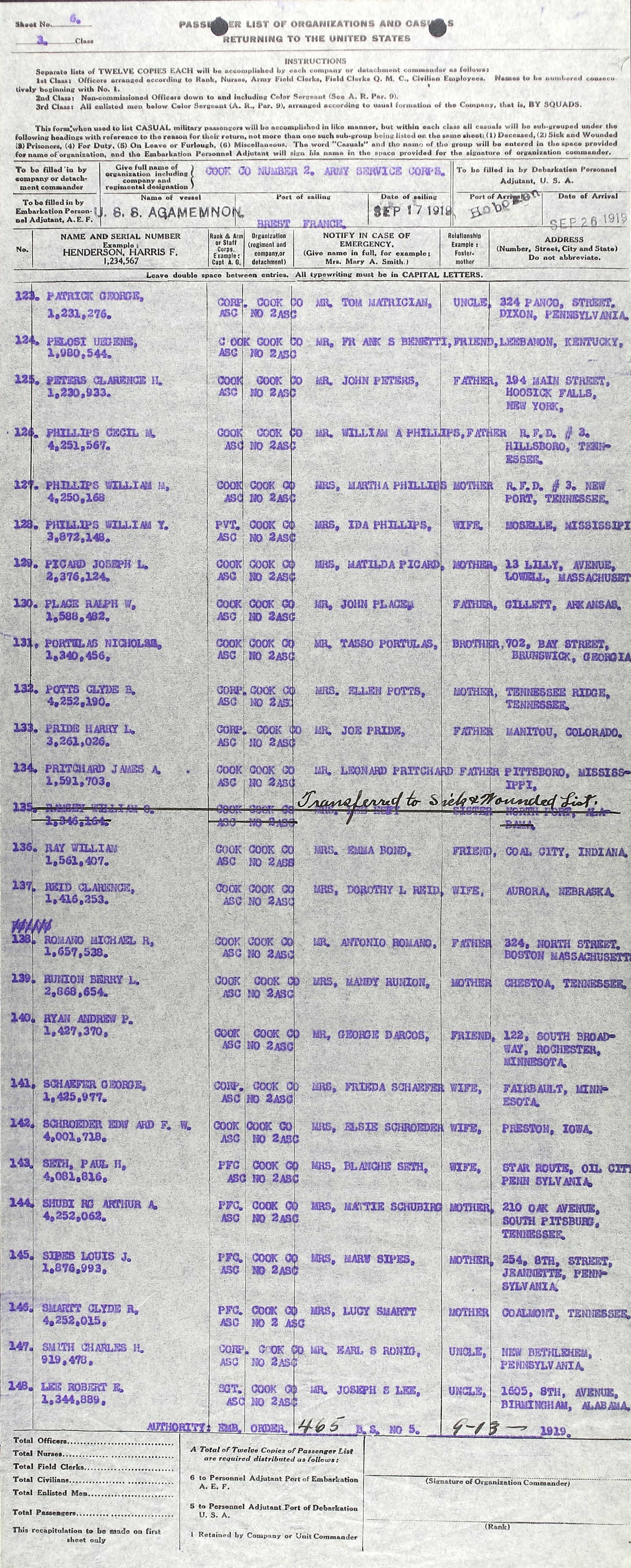

From Le Mans, we don’t where the Army took Uncle Clyde. All we know is that Potts, Clyde B., returned to the US, from Brest to Hoboken, aboard the Agamemnon one year later. In that time, he had been promoted to corporal and made a cook in the Army Service Corps.

Clyde Brake Potts aboard the Agamemnon

Clyde Brake Potts aboard the Agamemnon

Back home, his brothers may have chided him for being a cook, but their little brother outranked them.

An intimate account of a soldier’s experience in World War I, A VERY MUDDY PLACE takes us on a journey from a young man’s rural American hometown onto one of the great battlefields of France. We follow Private B. F. Potts with the 137th US Infantry Regiment through the first days of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. We discover a personal story—touching, emotional, unforgettable.

In 1918, twenty-three-year-old Bennie Potts was drafted into the US Army to fight in the World War. He served with the American Expeditionary Force in France. At home after the war, he married and raised a family, and the war for his children and grandchildren became the anecdotes he told them.

A century later, a great grandson brings together his ancestor’s war stories and the historical record to follow Private Benjamin Franklin Potts from Tennessee to the Great War in France and back home again.

A Very Muddy Place

WAR STORIES

Gibson, E. W., “Leviathan a Charnal Ship,” reproduced on the Cow Hampshire: New Hampshire’s History Blog

Crosby, Alfred W., America's Forgotten Pandemic: The Influenza of 1918. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2003

Rinaldi, Richard A., The United States Army in World War I: Orders of Battle, Ground Units, 1917-1919. Tiger Lily Publications 2005

Forte’s letter is reproduced in a submission by Pat Kelly, CAPT, USN, Ret., on the East Tennessee Veterans Memorial Association website.