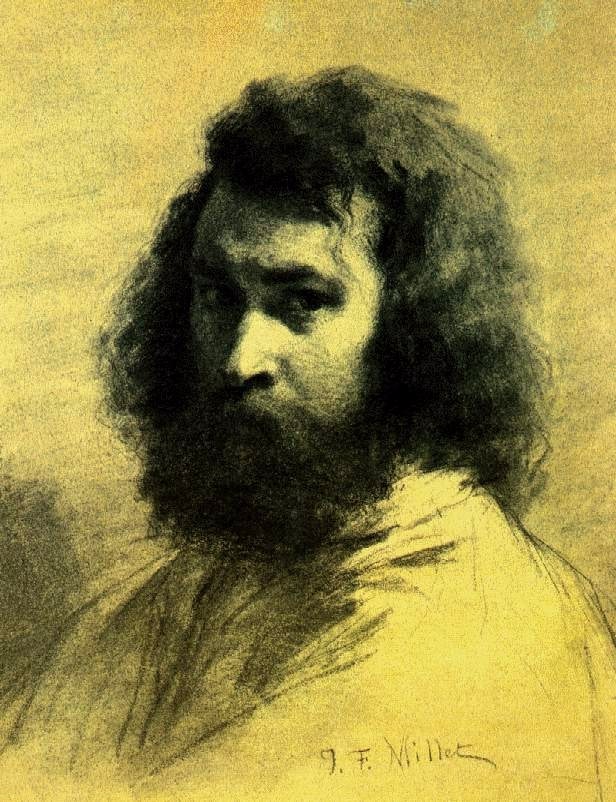

“You don’t mean the Jean-François Millet who painted The Angelus?” she said.

I was trying to tell Catherine a fantastic story about an artist I had just read in a book and was making a mess of it. There were many details and I had the order of their presentation all wrong. I showed her the book cover.

Cover of The Barbizon Diaries by James A. Owen, showing Millet’s Sower

“The Sower was one of his paintings,” I said. “He had a studio in Barbizon.”

“That’s him. Millet is one of the great French landscape painters and L’angélus,” she used the French name, “is his most famous painting. You say your friend, James, is related to him?”

“Distantly.”

From the second and third books of James A. Owen’s Meditations Trilogy, the story of The Millet Fresco is really more of a legend. According to the author’s own admission, it is rumor and hearsay from across the ocean and passed down through the generations on his mother’s side of the family. It’s intriguing, nonetheless.

In an effort to get it more or less correct, I’ll summarize the story, first, then I’ll add some details.

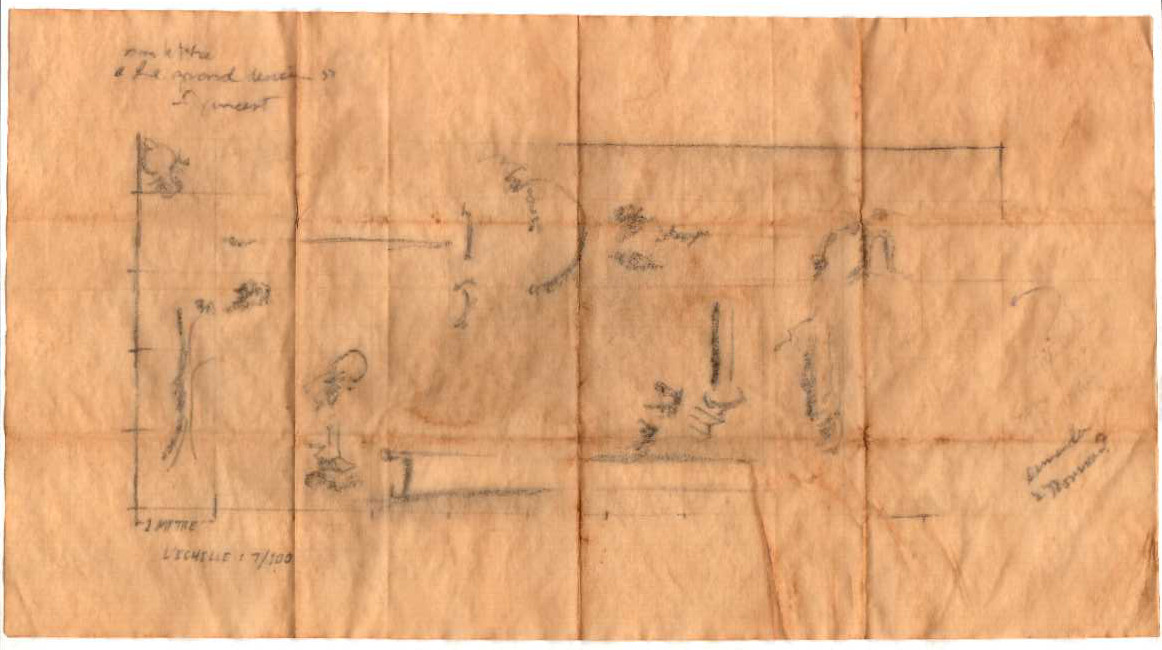

A group of painters met at an inn in rural France where they decided to make a fresco. The project apparently never got past the planning stage. However, a journalist present at the meeting took some notes that described the meeting and the sketch one of the artists made of the planned fresco. The notes eventually came into the hands of a distant American cousin of the sketch-making artist. This cousin, a painter himself, was hooked on the idea of painting the fresco and so spent the rest of his life searching for the sketch described in the journalist’s notes. He never found it.

A mundane story, perhaps, but now the details.

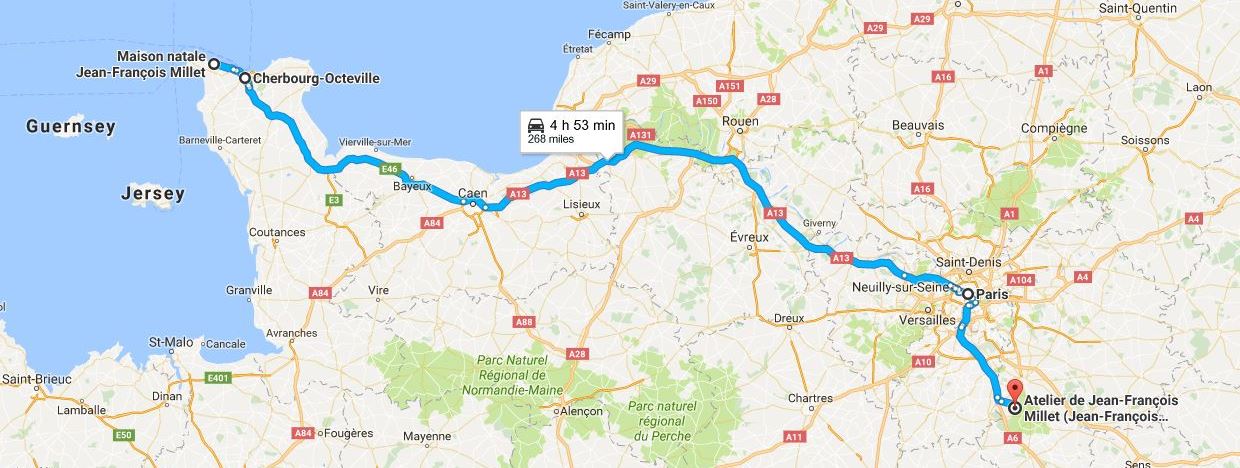

According to Owen, the meeting of the painters took place following dinner one evening at an inn located in the French village of Barbizon. The date is unknown, though it may have been sometime during the 1870’s. Among the group was Vincent van Gogh and other now famous artists such as Gauguin, Cézanne and Seurat, in addition to Jean-François Millet. It was Millet who supposedly made the sketch of the planned fresco in collaboration with the others.

Robert Louis Stevenson was the note-taking journalist, and Millet’s distant American cousin who eventually got hold of Stevenson’s notes of the evening was named Francis Davis Millet. Finally, Stevenson’s notes came to F.D. Millet by way of none other than Mark Twain.

From mundane to extraordinary, and it gets better.

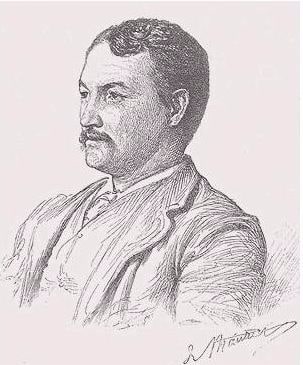

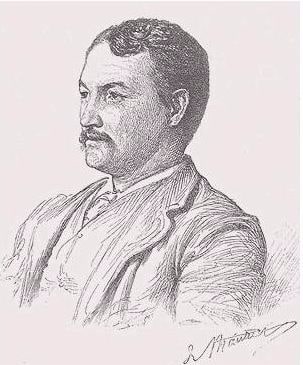

Portrait of Francis Davis Millet by George du Maurier, from Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, June 1889

Though probably the least well-known of the names above, Francis Davis Millet is a notable character in his own right. In addition to painter, we can also count sculptor, architect, journalist and war correspondent among the man’s many talents. He traveled as far as Russia and the South Pacific, ostensibly on journalistic business, though possibly in search of the fresco sketch. In 1912 on a trip from Europe to New York, Millet booked passage on the maiden voyage of the largest ocean cruise liner ever put to sea at that time, the Titanic. He did not survive its sinking in the North Atlantic, nor presumably did Stevenson’s notes.

Again, Owen admits that the story is a family legend. There is no hard evidence of any truth to it whatsoever. Explorers know, however, that a legend often has a kernel of truth hidden inside it, like the grain of sand at the center of a pearl. During my journey to Barbizon, I will certainly keep an eye out for it.

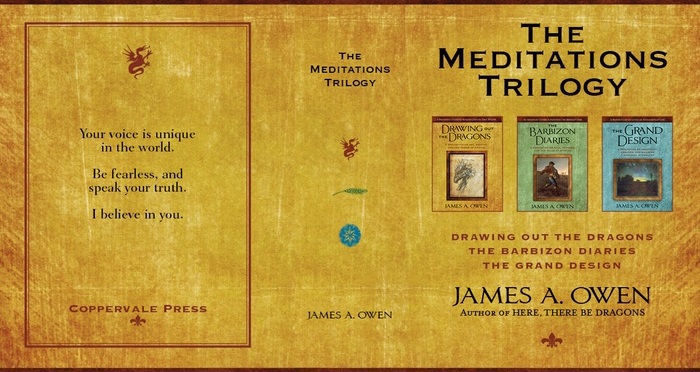

Despite my focus here on the legend of The Millet Fresco, James A. Owen’s Meditations Trilogy is about finding and pursuing your purpose in life. The hardcover books, Drawing out the Dragons, The Barbizon Diaries and The Grand Design, are soon to be available by Coppervale Press in a slipcase set.